Bukhara@45: Inside story of the most successful Indian fine-dining restaurant

It is difficult to imagine a restaurant that has not changed over the past 45 years. It has the same seating (which some find uncomfortable), the same crockery and cutlery (you get to use the latter only if you insist on going against its fingers-only policy), and the same menu presented on the same wooden boards by waiters dressed just the way they were when it first opened its door in 1979.

Even the name — Bukhara — is inappropriate for a restaurant that has built its reputation and fortunes on North-West Frontier cuisine. Rightly, it should have been named Peshawari, which is what it is called outside Delhi.

Bukhara at the ITC Maurya, the luxury hotel located on Delhi’s busy Sardar Patel Marg, has also not seen its profit-and-loss figures change in the last 45 years — it continues to be the country’s highest-earning restaurant and its waiting period is the stuff of legends about the palms that need to be greased and strings that have to be pulled to be able to jump the queue. A friend once confessed that even a call from the PMO did not help him.

The man who conceptualised Bukhara was the brilliant Ajit Narain Haksar, who as chairman of the tobacco giant, ITC, was responsible for its diversification into hotels. He was quick to figure out that none of the handful of five-star hotels operating in Delhi in those days had a restaurant that could match the popularity of Moti Mahal, where the Capital’s elite went to satisfy their cravings for tandoori chicken and ‘maa ki dal’.

Close to Moti Mahal, at the now-defunct hotel, The President, there was a popular haunt for kebabs called Tandoor, and The Oberoi, which was then an InterContinental hotel, had The Mughal Room, which got lost because of its location in the basement.

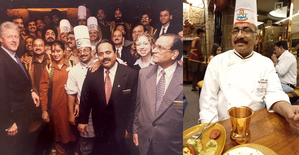

Haksar set his sights on Madan Lal Jaiswal of Tandoor and from the front of the house, he poached the colourful maitre d’ of The Mughal Room named Todar Mal. They were joined by Imtiaz Qureshi, who later became an institution in himself and was awarded a Padma Shri (the first chef to be so honoured), and invented one of Bukhara’s standouts, the Sikandari Raan. Together, they put together a menu that remains unchallenged till this day, its stars being Dal Bukhara, Barrah Kebab, Tandoori Prawns and the unique Tandoori Phool with cauliflower florets.

And if the restaurant has been able to maintain its unassailable lead, it’s because of its anal obsession with consistency.

Bukhara’s Executive Chef, J.P. Singh, who took over from Jaiswal after he died tragically in a road accident in 1991, told IANS that if the prawns are not within the range of 80 to 100 gms, or the chicken for the Murgh Malai Kebabs do not weigh between 60 and 70 gms apiece, the pieces are dispatched to the other restaurants of the hotel.

Even the humongous Naan Bukhara, which easily fills up half a table, has been made with one kilo and 300 gms of dough, and is heated in the tandoor for eight to ten minutes for as long as people working at the restaurant can remember. And like all else at Bukhara, both Singh, and the majority of the staff, have been constants in the restaurant.

In ‘Bite the Bullet’, his autobiography, Haksar, who, incidentally, was related to Indira Gandhi’s powerful private secretary, P.N. Haksar, says he got the idea of people eating with their hands and wearing aprons, instead of spreading a serviette on the lap, after seeing a BBC TV series on the life of King Henry VIII. If English royalty could eat with their hands, why couldn’t we, he reasoned with himself, and the practice has been in vogue since the day Bukhara opened. The practice even survived one of the early (and rare at the Maurya) European manager’s attempts to do away with it!

According to Haksar, the seating (conspiracy theorists insist the design is driven by the idea of making people leave as soon as they finish eating!) and decor were inspired by a World War II film set partly in the North-West Frontier.

There was a scene in it, Haksar writes, where British officers were seen dining at a rugged local eatery. The image stayed in Haksar’s mind when he was conceiving Bukhara with Rajinder Kumar, the architect who became famous after the Maurya came up.

Haksar also borrowed the idea of the glass-fronted kitchen (which was a novelty in its time) from Rama International, a hotel in Aurangabad, Maharashtra, that ITC managed for Iqbal Ghei and Pishori Lal Lamba (who became better known in Delhi for the Connaught Place restaurant, Kwality).

In fact, Kumar, the architect, had designed Rama International and therefore knew about how difficult it was to have a glass-fronted kitchen with two flaming tandoors belching out liberal quantities of smoke and emitting unwelcome smells. In his memoir, ‘Borders to Boardroom’, Habib Rehman, who headed the Maurya and then ITC Hotels in their formative years, talks about the challenges posed by the innovation, the biggest being insulating the glass front from the scalding heat of the tandoors.

Despite these many challenges, Haksar’s vision prevailed and Bukhara continues to be run the same way as it was in 1979, barring a couple of significant changes.

Bukhara started as a 60-seater (it has 130 seats today) and its entry was through Amrapali, the coffee shop that was subsequently renamed Pavilion (and was famous in its time for its ‘chaat trolley’). The strange layout had an adverse effect on the image of Amrapali, for there would always be a little crowd of Bukhara diners hanging about, awaiting their turn or even ordering starters from their favourite restaurant.

Thanks to the 1982 Asian Games, when the hotel underwent a major refurbishment, this layout was altered — and little has changed since then. It doesn’t have to, for at Bukhara, there’s never a dull day, and as they say, if it ain’t broke, why fix it?