When writer and realist actor Balraj Sahni raced against a train for a film scene

More than three decades before Aamir Khan’s train stunt in “Ghulam” (1998), this actor, renowned for his natural performances, had already done such a hazardous exploit, not just a daredevil challenge on the screen, but to inject reality into the scene and save the filmmaker the “bother of back projection”.

Balraj Sahni also involved Meena Kumari in his risky ruse in “Pinjre ke Panchhi” (1966), which — in another strange resemblance with Aamir’s film — was shot at Khandala. The scene had her walking on the rail tracks in a bid to commit suicide, even as he ran after her and managed to pull her aside from the rushing train at the last minute.

The filmmaker only wanted shots of him running after her and pulling her away; those of the were to be juxtapositioned. Sahni, however, knew that a train would pass the spot soon, and if they moved fast, the whole scene could be filmed there only. He asked the director, who, in turn, asked the actress, and she gamely agreed.

With all arrangements in place, he started chasing Meena Kumari amid shrill whistles from the approaching train’s driver, who “must have been horrified to see us right in the middle of the track”. The train must have been only a few yards away when Sahni dragged Meena Kumari away, he recalled in his autobiography “Meri Filmi Atamkatha”,

The shot came out perfect, but Sahni, who was above 50 then, only later realised how he had imperilled both of them. Going to her hotel room to apologise, he found her sitting with her head in her hands and she asked him if he was tired of life. He acknowledged his recklessness but also questioned why she went along.

“You were so very keen on taking that shot at one go! How could I then stop you?” was her disarming response with a rare smile.

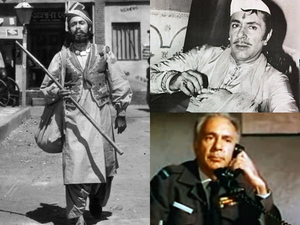

This aim of realism marked the film career of Balraj Sahni, born on this day (May 1) in Rawalpindi in 1913. He may not have been Hindi cinema’s first ‘natural’ actor — that honour was for near-contemporary Motilal — but was matched by few when it came to researching his roles, which spanned from a dispossessed peasant to a rich landlord, among others.

He nearly missed his iconic role in “Do Bigha Zameen” (1953), when a bemused Bimal Roy nearly sent him off after Sahni landed at his office in a London-made suit. But he convinced the exacting filmmaker and prepared for the role of a farmer-turned-menial labourer by living — and working along as Deen Bandhu — with the rickshaw pullers of Calcutta to familiarise himself with their language, mannerisms and habits.

Before this, Sahni, jailed in a political case, notched up an unparalleled record by being allowed to leave the prison in the day, under guard, to shoot for a film — where he played the role of a jailor! This was K. Asif’s “Hulchul” (1951), starring Dilip Kumar and Nargis.

Like many others of his generation, he was enamoured of films and came to Calcutta to join New Theatres after he completed his post-graduate studies at Lahore’s Government College in 1936. It did not work out and he went back to the family business in Rawalpindi.

The next year, he was back in Calcutta, with wife Damyanti, and they became language teachers at Viswa Bharati, interacting with Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, who suggested the name of their son (Parikshit, born in 1939).

The Sahnis also taught at Mahatma Gandhi’s Sevagram before reaching London in 1939 where he became a Hindi broadcaster for the Indian Section of the BBC’s Eastern Service.

Here, he made the acquaintance of George Orwell, and in January 1942, read out his “The Meaning of Sabotage”, ostensibly addressed to the conquered people of Europe — but with wider ramifications for other colonised populaces. He also convinced BBC to feature Indian music, particularly K.L. Saigal.

The couple returned to India in 1943, and he was at bit of a loose end when old friend Chetan Anand invited him to come to Bombay to join films. Sahni made his debut with “Dharti Ke Lal” (1946), based on the 1943 Bengal famine, though most such films before “Do Bigha Zameen” were nondescript.

His 125-odd later films, including at least two in Punjabi, comprised social dramas such as “Seema” (“Tu pya ka sagar hai”, 1955), “Chhoti Bahen” (1959), and “Kabuliwala” (1961), offbeat love story “Anuradha” (1960), war dramas “Haqeeqat” (1964) and “Hindustan Ki Kasam” (1973), and lost-and-found tales like “Waqt” (“Ae meri zohr-e-jabeen”, 1965) and the distressing “Garam Hawa” (1973).

A writer too, Sahni, who passed away in April 1973, had half a dozen books in both Hindi and Punjabi to his credit — and some of the latter are still on the syllabus in Punjab universities.